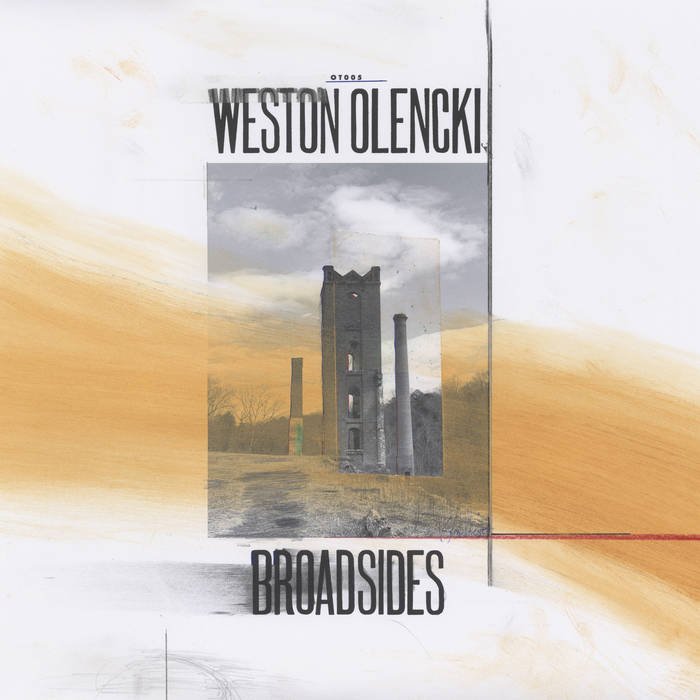

Weston Olencki, “Broadsides” (Outside Time, 2025)

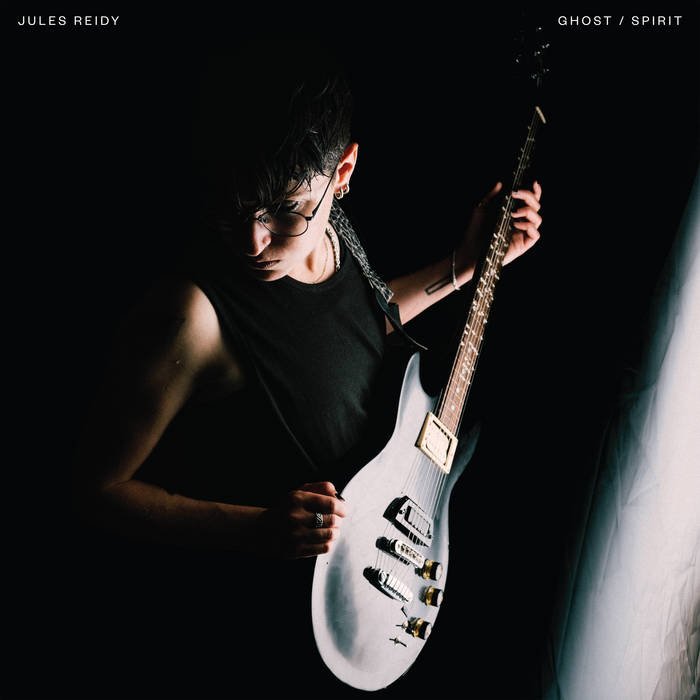

This is the first solo album that I have heard from this Berlin-based composer, but I have previously enjoyed his collaborations with Tongue Depressor and Jules Reidy. Notably, the latter (2024’s I Went to the Dance) was a continuation of the “avant-hillbilly” era that first began to take shape with 2022’s Old-Time Music and now returns in spectacular fashion with Broadsides. While Olencki’s primary inspiration remains firmly rooted in the rural American South and Appalachian folk music traditions, these latest pieces present that vision in more of an intense and complexly layered sound collage experience that lands somewhere between a maximalist Chris Watson and a killer Daniel Bachman/Francisco Lopez mash-up. It also happens to be one of the most mesmerizing and immersive headphone albums of the year.

This album can arguably be described as an abstract and impressionistic diary of Olencki’s 2023 trip across the American South, as it was lovingly assembled from field recordings taken along the way (rivers, crickets, trains, etc.) and deconstructed bluegrass and country standards. Notably, the South is a place of deep personal meaning for Olencki, as they grew up in South Carolina and now live in a dramatically different culture half a world away. In keeping with the “deeply personal” theme, Broadsides’ structure is also inventively informed by their family’s generational passion for quilting, as Olencki notes that ““Quilting, like music, is a practice of embedding knowledge and remembrance into the very core of the thing you are making.” In the case of Broadsides, that means that these complexly woven collages pull in all kinds of childhood memories, cherished places, and familiar old songs from the past, as well as plenty of new sounds and impressions from the road trip experienced as an expat reshaped by life in a German city.

Fittingly, the journey begins with the immersive and vividly realized sounds of a train station (“Prelude”), but things start to veer off the tracks in supremely hallucinatory fashion by the second half of “she left,” as the sounds of rain storm blossom into a dizzying and endlessly churning maelstrom of layered textures. Headphone listening is absolutely essential, as the magic of the piece lies in the cacophony of visceral, sharply realized textures and the seemingly infinite subtle transformations lurking within. It is the following “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” that is the album’s stunning centerpiece, however, as gently sloshing waves and a loose and casual banjo improvisation gradually blossom into an absolutely bananas banjo supernova.

Much like its predecessors, it is more of a rich sensory experience than a melodic song, but Olencki’s increasingly wild and violent banjo playing sounds like a desperate attempt to beat the devil. Described as “the euphoria of melancholy in motion,” Olencki achieved the piece’s delirious intensity via computer, as the “plucks of banjo are bounced around the frame by a computer, its pitches determined within algorithmic sequences and transcriptions of classic three-finger licks.” Amusingly, the piece ends with a non-computer-enhanced recording of some old-timey fiddlin’, which makes me feel like I’ve just stumbled dazedly out of a diabolically unhinged square dance.

The album’s other stunner is the following “all my fathers clocks,” as the overlapping clockwork rhythms of several antique clocks provide the backdrop for an absolutely feral bowed autoharp performance (purchased from a local strip mall and left detuned). Like every other piece, it is primarily an immersive experience, but this one is an intensely gnarled and visceral celebration of creaks, buzzes, sweeps, and bow scrapes. Notably, it is also quite a bit more nightmarish than the rest of the album, as it pointedly departs from the rural and rustic atmosphere of the earlier pieces to approximate a ferocious and incendiary noise set by a demonic cellist. Elsewhere, the closing “Omie Wise” is a highlight in a very different vein, as an increasingly warped and phantasmagoric pedal steel performance from guest Henry Birdsey is joined by river sounds and buried renditions of the titular murder ballad that serve more of an ASMR function than a melodic one.

While the river sounds were fittingly recorded from the same river where Naomi Wise’s body was found, the murder ballad aspect does not darken the piece all that much, as it mostly just feels wonderfully disorienting and dreamlike before everything falls away for a lovely and transcendent outro in the form of a crackling and skipping recording of the hymn “How Great Thou Art.” It makes for a perfect ending to a singular, poignant, and wildly ambitious album. While I could probably rave about the vivid and wonderfully textured production and mixing at length (Broadsides is an absolute a tour de force in that regard), I will valiantly restrain myself from that, as Olencki’s larger achievement lies in crafting the kind of album that leaves me feeling like something profound, uplifting, and vaguely life-changing has just occurred.

Listen here.