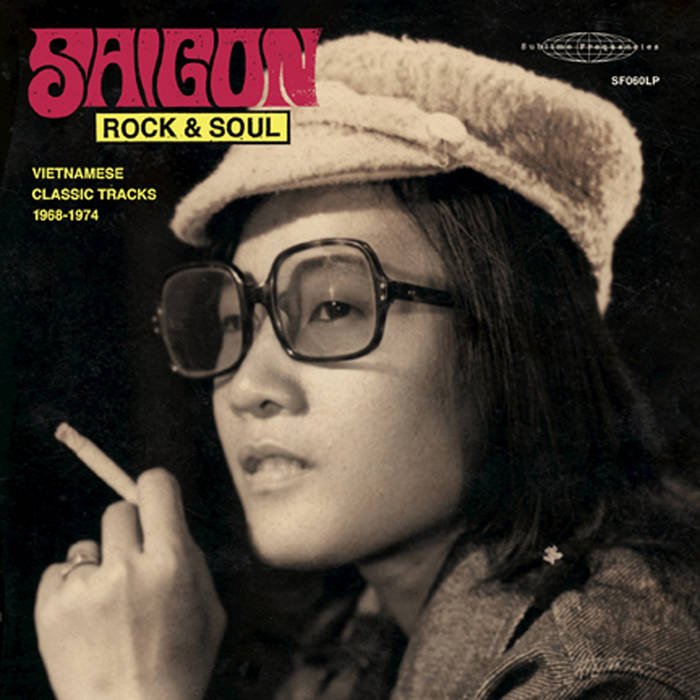

“Saigon Rock & Soul: Vietnamese Classic Tracks 1968-1974” (Sublime Frequencies, 2010)

In characteristic Sublime Frequencies fashion, Mark Gergis’ latest compilation documents a truly unique and flourishing scene that very few people even knew existed. It is hard to think of many positive things that came out of the Vietnam War but the free exchange of music and equipment between American soldiers and Saigon’s hipper young musicians certainly resulted in some raucous and inventive music that could not have otherwise existed. Punk would have had no reason to happen if rock music had been this wild in the Western world in the mid-’70s.

This is the sort of album that could only have come out on Sublime Frequencies for many reasons, but the main one is that compiling such a retrospective seemed like such a complicated and near-hopeless task: these songs were essentially wiped from the earth after Saigon fell to the Viet Cong in 1975. Some musicians were tipped-off by friends and were able to flee the country to continue their careers as nomadic rock n’ roll refugees, but the ones that stayed behind were forced to destroy any evidence of Western culture to avoid being dispatched to reform camps.

Further complicating the endeavor was the fact that Southeast Asian cultures have a tendency to view pop music as a disposable and very of-the-moment thing. Even if this music had remained available, most Vietnamese music fans wouldn’t have cared or noticed. They are interested in what is happening now, not forty years ago (“fetishism of the old is left to those rare creatures obsessed enough to take on the task”).

As if that wasn’t enough, any new interpretations are viewed as supplanting the original versions, making Internet searches an exasperating process. Consequently, original recordings from that short-lived era are staggeringly difficult to come by in 2010, even without a language barrier standing in the way. Fortunately, Gergis was aided in his efforts by a California record collector named Rick Foust who had presciently snapped up a lot of these recordings when they were available in Vietnamese-owned shops in the ’80s.

Gergis definitely tried to give a broad overview of the scene, which necessarily means that listeners will probably not fall in love with every single song. On the flip side, however, it is hard to imagine anyone who loves music not being floored by at least one or two pieces here. I personally had a hard time embracing some of the more high-pitched vocal performances, like the one in the CBC Band’s opening “Tình Yêu Tuyệt Vời (The Greatest Love).” That said, the band themselves rip shit up quite impressively (the liner notes describe them (quite rightly) as “teenage acid rock of the highest order”).

Admittedly, acid rock is generally not a favorite genre of mine, but these teens were smart enough to replace its more plodding and self-indulgent aspects with infectious youthful exuberance and a rumbling, funky low-end. It is damn near impossible not to love a band that is so obviously intent on unleashing a raucously hell-raising good time. Sadly, even though Rolling Stone once proclaimed them to be “The Best Band in the Orient,” they only ever managed to record two songs (for the soundtrack to a comedy, no less). In keeping with that theme, the band (now living in Texas) were absolutely stunned that Gergis unearthed those songs, as even they themselves hadn’t heard them in nearly four decades.

The most essential piece on the album, however, is probably Connie Kim’s incendiary “Anh Đâu Em Đó [Where You Are, I’ll Be There],” which features one of the absolute best rhythm sections that I have ever heard. The groove is so perfect that the rest of the band could have been playing literally anything and it wouldn’t matter, but everything else is great too: wild organ solos, smoky saxophones, fuzzed out guitars, and cool sultry vocals. I imagine that it must have been a bit disorienting for some G.I.s to come back home and hear the comparatively neutered rock being played on radios in the US after experiencing such funky, frenzied abandon abroad. That said, there are a number of other stunning pieces strewn throughout the album that take wildly different stylistic paths, such as Hoàng Oanh’s languidly melancholy “Ngày Sau Sẽ Ra Sao,” the mutant Motown girl-group pop of Thai Thanh, and Thanh Lan’s suavely cosmopolitan “Hoài Thu [Autumn Memory].”

As with just about all Sublime Frequencies releases, the sound quality is quite raw. Fortunately, that actually works quite effectively in this case, as this music deserves to be heard as it was experienced in those steamy Saigon clubs forty years ago: gritty and unfiltered. Most of these artists rely heavily on sinuously funky bass lines and overdriven and wah-wah’ed guitars, both of which only sound more visceral with increased volume and in-the-red recording quality.

While I am usually not a fan of foreign pastiches of American rock in general, the sheer enthusiasm and passion of these musicians managed to burn through my misgivings beautifully and instantly. Saigon Rock & Soul captures a singular cultural nexus: the thrill of discovering rock and roll colliding with the urgency of living in the midst of a war zone. This is some of the most thrillingly alive music that will be released this year (and one impressive feat of musicology to boot).

Listen here.

Note: Two tracks were misidentified on the original release. On track B4, Hoàng Oanh and the song “Ngày Sau Sẽ Ra Sao” were misidentified as Lệ Thu and the song “Sao Biển.” On track C3, Connie Kim and the song “Anh Đâu Em Đó” were misidentified as Băng Châu (misspelled as Bang Chan) and the song “Những Đóm Mắt Hoả Châu.”